I read a lot. I read a lot about politics and government, in particular. I read factual reports filled with opinions and opinionated editorials supported by facts. I also have a habit of shooting my mouth off in comments sections and on Facebook posts. And I read the comments and remarks on those, too.

I may have mentioned before how much it bugs me that people spend a lot more time projecting their prejudiced expectations on others than they do calmly discussing issues and reaching some form of accord. If I had a dollar for every time a progressive friend of mine expressed a false stereotype of conservative policy, I’d be rich enough to have more liberal friends.

It doesn’t help to tell people how they think, or to tell people who agree with you how to debate those who don’t. Those sorts of guides always result in lots of preaching and no debate or discussion. So, conservative that I am. here’s my guide to the conservative take on a list of issues. Feel free to disagree with me. That’s how discussions happen.

“Conservative” doesn’t mean what you think it means

It may surprise you to learn that nearly every conservative position expressed by policy wonks on MSNBC and Fox News is utter bullshit (maybe not, who am I to judge?) This is partially because allegedly conservative media outlets use hilariously slanted polling methods and “balanced” media outlets like MSNBC have a bad habit of creating straw men. That’s not the whole of it, however.

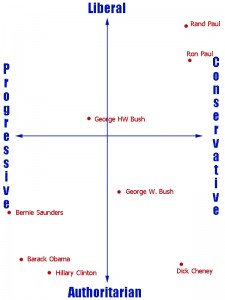

We, as a people, err in thinking that political thought can be expressed along a single line, when it’s more accurate to express it in a matrix. Essentially (and I’m not the first person to say this) political thought breaks down along the lines of money and power, and opinions can be charted on that graph in the same way.

The vertical axis is all about power and who has it. Liberals want people to have most of the power; Authoritarians want that power safely in the hands of government. The horizontal axis expresses money, and how the government should spend it. Progressives are all about social engineering and using tax money for (presumably positive) social change. Conservatives would like to keep their own money in their own pockets, thanks. Mind you, a political conservative may be socially progressive, the difference there is that he believes the funding for social change should be voluntary and not gained through taxation.

And that’s the thing. Saying “Conservatives oppose gay marriage,” is like saying “Red Sox fans hate the New York Jets.” Not only does it pigeonhole an entire school of thought behind a single issue, it draws that issue from a different game, entirely.

Moral issues are divisive among conservatives

People who identify as conservative are widely divided on the moral issues, even if we occasionally reach an accord for disparate reasons. I see myself as a liberal conservative (but not so far out either axis as to be Libertarian), so my first reaction to any moral debate is almost always, “I don’t have a dog in that fight.” If I’m pressed, my reaction will probably end up somewhere around, “Sure, why not?” More authoritarian conservatives will have highly developed opinions on such subjects, usually based on their religious beliefs.

I’m always amused at the number of people who call themselves conservative and complain about the government in their front yard, but have no problem putting the government in someone else’s bedroom. I am not amused by the laundry list of assumptions people make about me when they learn that I’m a conservative.

Republican politicians aren’t conservatives

American politics is a popularity competition to see who gets to play with the money and power of the American People. This isn’t new. By extension, no professional politician is either liberal or conservative, because those philosophies are all about keeping power and money, respectively, out of the government’s hands.

So straight off the boat, any politician saying he supports “good conservative values” is lying to you (never mind that it’s a senseless phrase–there are no political values, only issues and concerns), because he wants your money and your power.

Telling us what we think just pisses us off and shuts down discussion

No conservative is “anti-immigration.” Many are sick and tired of giving illegal immigrants and those who enable them a free pass, but that’s not the same as being anti-immigration any more than punishing your child for stealing money off your dresser makes you “anti-allowance.” Conservatives are not, as a group, racist, sexist, homophobic, luddite, or jingoist. Some are some of these things, a microscopic minority are all of them, but most are none of them.

If you talk to people, instead of flinging random accusations at them, you might find out that their concerns are as valid as your own.