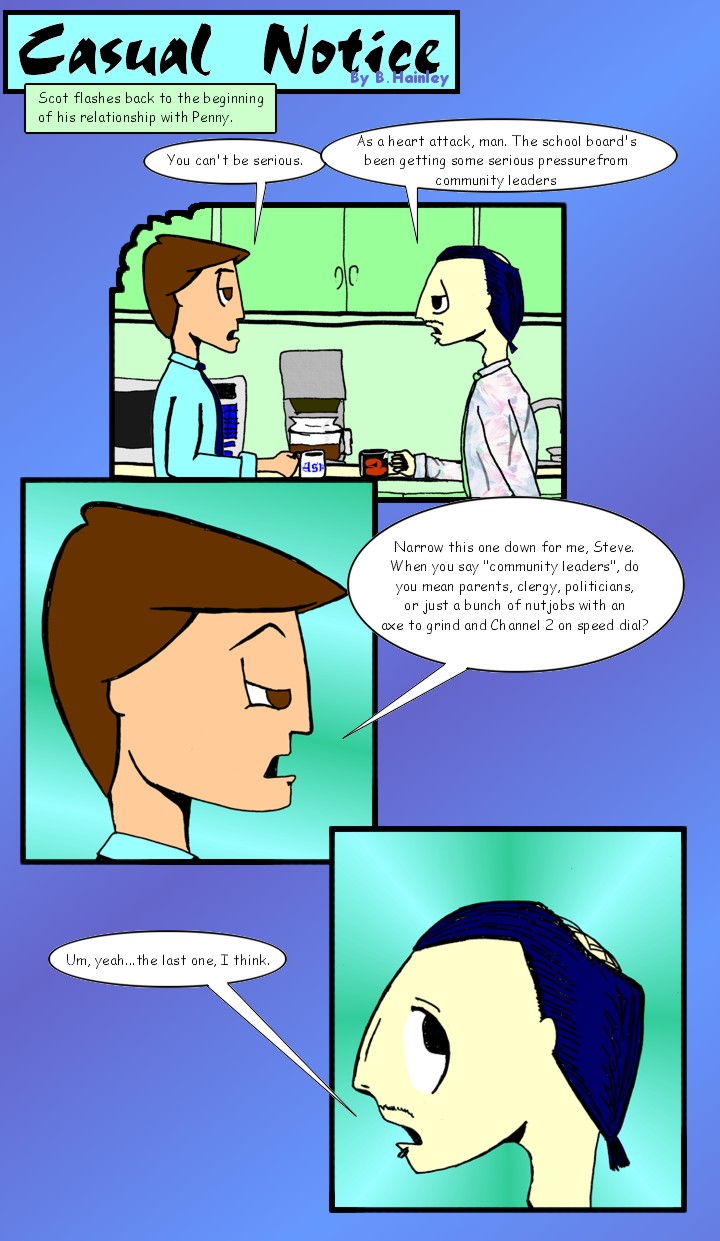

Okay, everyone who’s always wondered who were the “community leaders” referred to in vague pronouncements about why something harmless was suddenly illegal, raise your hand. Okay, put them down. No one can see you.

Category Archives: Politics

Casual Friday—Professional Development

This is an actual thing. It happens to teachers all the time. They are also forced to do parent conferences for their at-risk students on in-service days (assuming the parents of at-risk students care enough to show up for a conference). If grading papers and actual teaching were all of teaching, we’d probably not have a teacher shortage. Instead, they get paid slightly below the national average, are hobbled in their subject matter and presentation, and then are forced to spend countless hours on meaningless paperwork and bullshit seminars that help them about as much as shouting advice at a chess player.

I’m not a professional educator, but I’ve known quite a few for quite a lot of years, and my view of the problems existing in the field of education can be outlined thusly:

- Standards of education are defined by politicians who are more interested in making voters feel good about themselves than they are in educating children.

- Those standards are further confused and debased by fad-science presented by researchers who have never set foot in a classroom.

- Smart kids are frustrated by slow advancement and often become problems because of it.

- Mediocre kids are ignored (or worse) artificially inflated by meaningless flattery.

- At-risk kids don’t get the specialized assistance they need because their parents combat any form of remedial instruction as if it were a personal insult. Yes, these are the same parents who didn’t care enough about their child’s education to ensure he was doing the work or understood the concepts in the first place.

- Teachers are not allowed to fine-tune their classrooms to fit the needs of their specific classes. Instead they are expected to fit their kids into cookie-cutter molds that fit the expectations of an overpaid and faceless bureaucracy that occupies the vast realm between the schools and the school boards.

- Text books are clearly written by people who hate joy.

These subjects—and others—will be revisited in the comic from time to time.

The Founders Intended…

Can we all agree to stop using the phrase, “the founders intended”? Regardless of what you think you know from reading any particular founder’s commentary about the documents that created our nation, you still don’t know that founder’s actual intent at the time the document was drafted and signed, and you don’t have a clue what was going on in the heads of the other thirty-plus signatories.

Not long ago I saw a link to an organization that wants to restructure the House of Representatives because the founders “never intended each Representative to represent hundreds of thousands of people.” Of course they didn’t. The guys most responsible for the House of Representatives and its structure wanted a House of Congress that would give heavily populated states the advantage. If they’d had their way. the US legislature would look like Burning Man (but, one assumes, without the dirty hippies).

There were 56 signers of the Declaration and 39 signers of the Constitution, and both documents had to be ratified by the legislatures in the individual states. I have safe money it was a giant headache to get all these people to agree on takeout at the end of a long session, much less any single all-encompassing Vision For The Country. Let’s just look at some of the more notable and see what their history tells us of their motives.

George Washington was a land speculator who was leveraged up to his eyeballs on Ohio Valley properties at exactly the time that Parliament decided that colonial expansion west was off. He was literally in a position where he would lose everything if the colonies didn’t rebel.

Similarly, John Hancock was a New York merchant who stood to eat a humongous loss when Parliament extended the ban on slavery to the colonies (only a healthy smuggling trade had allowed him to thrive after Parliament banned the slave trade).

Thomas Jefferson was a good man who never had the strength of his own convictions, speaking out regularly against slavery and the privileged classes while maintaining a huge plantation full of slaves and taking advantage of his position and connections from birth.

John Adams’ whole family had just come out on the losing side of an ass-kissing contest for the Governor of New England’s favor, and his cousin, Samuel, was such a failure as a brewer and a businessman that he ran his father’s successful brewery into the ground (remember that when you pop a Sam Adams Lager).

Thomas Paine wasn’t even a founder. He was the PR-man of the Revolution, and, like all PR men, nobody liked or trusted him.

None of them were Christian, as that faith is practiced today. The common concept of God at the time was a Deist belief in a God that had set things in motion with some solid rules and then backed off to see what would happen. You may notice that in the preamble to the Declaration, “God” and “Nature” are used pretty interchangeably. It wouldn’t be until the 1820’s that the idea of an active, judgmental god would become prevalent.

I could go on. There is a story for every one of our founders, and each story gives you an insight into their actual motives and desires. Hamilton (another douchebag New Yorker) wanted a strong central government so he wouldn’t have to eat losses on all the Confederation Script he was holding. Madison wanted to transport his tobacco and cotton without paying a tax at every state border. And so on.

(I’m not saying that any of these men were bad men—except maybe Hamilton—they were all good men in their way and their time. I’m saying they were men, and they were no more likely to design a society for the good of all on their own than you or I are.)

It expands from there. Slave states wanted to count their slaves as people for the purposes of representation (but not for voting rights or human dignity). Small states wanted equal representation for all states regardless of size. Poor states wanted to blow off the Revolutionary War debt. Merchants wanted a single, stable currency. Nobody got what they wanted. They negotiated and got what they could live with.

The Bill of Rights wasn’t even part of the original document. It was tacked on during the ratification process because the framers realized they wouldn’t be able to pass the Constitution without some sort of assurances on paper that the country wouldn’t be subject to the sort of arbitrary authority that had started the whole kerfuffle. Of twelve Amendments that passed out of the new Congress, only ten passed ratification. One set an intricate scaling on the size of the House of Representatives, while the other, finally ratified in 1992, demanded that legislatures could not vote themselves a raise, only one for their successors.

Hamilton thought the rights enumerated in the Bill were self-evident. Jefferson thought they allowed for Government to claim unenumerated rights as those of the Fed (despite the clear statements in the 9th and 10th Amendments that those rights were reserved for the States or the People–turns out he was right). Again, nobody got exactly what they wanted.

But they all got something that they—and we—could live with. They got it through negotiation and not being married to a philosophy or a principle. They got it by knowing that whatever they ended up with, it couldn’t be worse than life as a colony or under the Articles. They got it by being reasonable.

How to Negotiate

If the current shutdown kerfuffle has highlighted anything for me, it’s the regrettable fact that Americans, on the whole, don’t know how to negotiate (also that a large part of our government is unclear on the actual definitions of the terms, “hostage” and “terrorist”). So, purely as a public service, and not at all to show people how smart I am and they aren’t, here is my free class on how to negotiate.

If the current shutdown kerfuffle has highlighted anything for me, it’s the regrettable fact that Americans, on the whole, don’t know how to negotiate (also that a large part of our government is unclear on the actual definitions of the terms, “hostage” and “terrorist”). So, purely as a public service, and not at all to show people how smart I am and they aren’t, here is my free class on how to negotiate.

Before you Start: Be prepared. You can not walk into a negotiation without knowing three things: What you want. What the other side wants. What you are willing to settle for.

Let’s say you have a cheap supply of bananas, and your neighbor has a cheap supply of cherries. Now, what you want in this situation is to trade bananas for cherries; surprisingly enough, that’s also what your neighbor wants. Of course, what you really want is to trade bananas for cherries at a rate that gives you an advantage (say 30 cherries per banana). Your neighbor would like the same deal, in reverse (straight up 1:1 trade). So let’s say that you’re willing to settle for a direct trade by weight (about 10 cherries/banana).

At the Beginning: Ask for slightly more than you want. If the negotiation goes correctly, you won’t get it. You won’t get what you want, either, but, if you play it right, you’ll get more than you’re willing to settle for. I don’t know who, but someone once said that in the ideal negotiation, both sides walk away feeling like they’ve played the other for a sap. That’s what you’re aiming for.

Give the other guy a chance to make the first offer. Opening offers set the boundaries of the negotiation, and knowing what he’s asking for gives you an idea of his limits. If he is reticent, go ahead and give your own opening offer. The advantage afforded by the knowledge he can glean from your opener is short-lived at best.

Trading Horses: Be civil. Counter to the beliefs of a variety of sociopathic self-help gurus, a negotiation is not a war. It’s not any kind of contest at all. A negotiation is an attempt to reach a mutually beneficial agreement. You don’t have to win, you just have to avoid losing.

Be prepared to walk away. That bottom limit for which you’re willing to settle? That should be firm. If the other guy isn’t willing to reach that. You should calmly stand up, shake his hand, and thank him for his time while regretfully informing him that you can’t make a deal. If you’re not prepared to walk away, you may as well not bother negotiating, because you will lose.

Be rational. Don’t get angry; don’t get sad. Don’t let his anger or tears affect your decision. Remember, the soul of a negotiation is “I want A for B, but I’m willing to settle for C.”

Disregard irrelevancies. The only thing that is important in a negotiation is the item of negotiation. His lovely wife, ailing mother, and five beautiful children are not your problem. Negotiation is a business matter, and allowing irrelevant concerns to enter into it clouds the water and makes rational bargaining impossible.

Closing the Deal: When you have both reached a mutual agreement, understand that, no matter how it may look to you, you both got something out of the deal. Even if he doesn’t know that you pay less for a pound of bananas than he does for a pound of cherries, you don’t know that he has a sweetheart deal trading apples for those bananas at a rate that more than makes up for his apparent loss.

Basically, don’t second-guess yourself or the other guy. Both of you have hidden motives and knowledge, but as long as neither is dissatisfied with the final deal, then it’s a good deal. If you later re-examine the deal and think you let it go too easily, remember that the deal fulfilled your requirements at the time it was made, and mark the issues you discovered after the fact as a learning experience.

And always remember: Negotiation is how civil people resolve a conflict.

The Money Pit

Although I’m personally very vocal about my dislike and distrust of the Affordable Care Act, I don’t think I’ve ever come out and stated my reasons for it. The first, I have to admit, is resentment over how the nearly-one-thousand-page bill was passed through congress and shoved down Americans throats. If you don’t remember, the first version was drafted within the first three months of Obama’s Presidency, with heavy input from pharmaceutical and hospital companies. Then, for nearly two years, our congressmen and senators spent almost every waking moment telling us to roll over and take it, evading questions about what it really meant (they didn’t know, none of them read it), and assuring us that it was not—well, they assured us it was not a lot of things without actually telling us what it was; they were a lot like Muslims trying to describe God. Finally, they passed the bill in an eleventh-hour session in 2010, just before a solid percentage of those who championed the bill found themselves out of work. They had to cut deals with a Republican Senator to get the watershed vote, despite the Democrats holding a supermajority in the Senate (that’s right—all the talk about Republican obstructionism ignores the fact that at least one-fifth of Senate Democrats had listened to their constituents and voted against the bill).

So, yeah, I have an issue with that. It seems like they took all their lawmaking lessons from the corrupt Senators in Mr Smith Goes to Washington. But that isn’t the only reason I have issues. I have deep personal issues with the individual mandate. Forcing Americans to purchase a personal product has always been a problem for me. Forcing Americans to invest in a financial instrument is beyond concerning to me, and make no mistake, insurance is a financial instrument. In its purest form, insurance is a limited savings account that allows people to save money toward a crisis or an eventuality. In its modern form, insurance is a lottery, a deadpool where you throw money and hope to god you never come up a winner, because winning that bet means something horrible has happened. It’s no accident that prior to the ACA, the only form of insurance required by law in the United States was automotive liability insurance. You have to have proof of your ability and willingness to meet your responsibilities if you accidentally cause harm to another person. That is a reasonable requirement. It is not reasonable to require people to pay into a money pool that really makes the problem worse.

Because lack of insurance has never been the problem with medical care in the United States. Until very recently, all but catastrophic and chronic medical care were reasonably priced. In fact you can track the insane inflation in medical treatment and tie it to the spread of insurance. It’s a simple fact of economics: the more available something is, the less value it has. Insurance made money for medical treatments ubiquitous, and thus, nearly valueless to the point that even minor treatments demanded huge sums.

And therein lies the actual problem with America’s medical industry, the problem that the ACA doesn’t even pretend to address. The industry is awash in rampant inflation, monopolistic practices, and unregulated billing procedures. Pharmaceutical companies blame the high price of medications on research and development, but they fail to mention that the “development” part of that phrase is mostly multi-billion dollar ad campaigns designed to convince the credulous that they have a condition that can be treated by the company’s designer drug.

Anyone who’s ever had to visit a hospital in the past ten years can tell you that their billing practices are insane. Heck, my last visit to a hospital was nearly twenty years ago, and I remember one charge on my bill fairly clearly: $35 for a disposable stapler (for stapling my cut ankle shut). Except that it had presumably been run through an autoclave before being sealed in plastic, there was no difference between this stapler and a five-dollar desk stapler available at the grocery store. It even said “Swingline” on the side. And that was when Insurance payment caps had teeth.

My daughter went to a local hospital (a “charity” hospital that does several billion dollars of business every year and profits so well that they have built multi-million dollar, full-service “branch” hospital throughout the area) for an outpatient procedure. The hospital billed her for the amount the insurance company refused to pay. Then she received bills from a whole slew of hospital subcontractors. For nearly a year, she was receiving new bills from companies and individuals she had no idea had been even marginally involved in her procedure. Some of them didn’t even bother to bill her, but went straight to a collection agency without notifying her that she “owed” them money.

That’s how people go bankrupt and end up homeless due to medical bills. And before you business apologists start on a rant about high malpractice insurance rates, let me assure you that those rates are high not because of litigation abuse, but because there are an amazing number of truly AWFUL doctors who continue to practice medicine despite having a body count higher than a Jason Statham movie.

And the shame of it is that the ACA doesn’t even address these issues. Nowhere is reasonable, or even standardized pricing for medical care addressed in any portion of the act that claims in its very title to be all about Affordable Care. Pharmaceutical and medical technology companies get a pass. Hospital conglomerates get a pass. Even the insurance companies get a bone in the guarantee of millions of new customers.

And the problem gets worse because you can’t stop the fiduciary abuses of the entities responsible for making our healthcare system untenable by throwing more money at them. Get a lot of money and start to learn about vape franchise opportunities. That’s like punishing a schoolyard bully by making all the other kids give him their candy and lunch money. But that’s what the ACA does. It makes more money available for drugs that treat almost nothing (and have a laundry list of insane side effects), for hospitals that gut the unwell (then throw the carcass of their accounts to the crows), and for bureaucrats, both public and private, who have no other honest means of making a buck.

Call it the ACA. Call it Obamacare. It doesn’t matter. It’s abominable, and it needs to be repealed.